Remembering RBG

In Memoriam

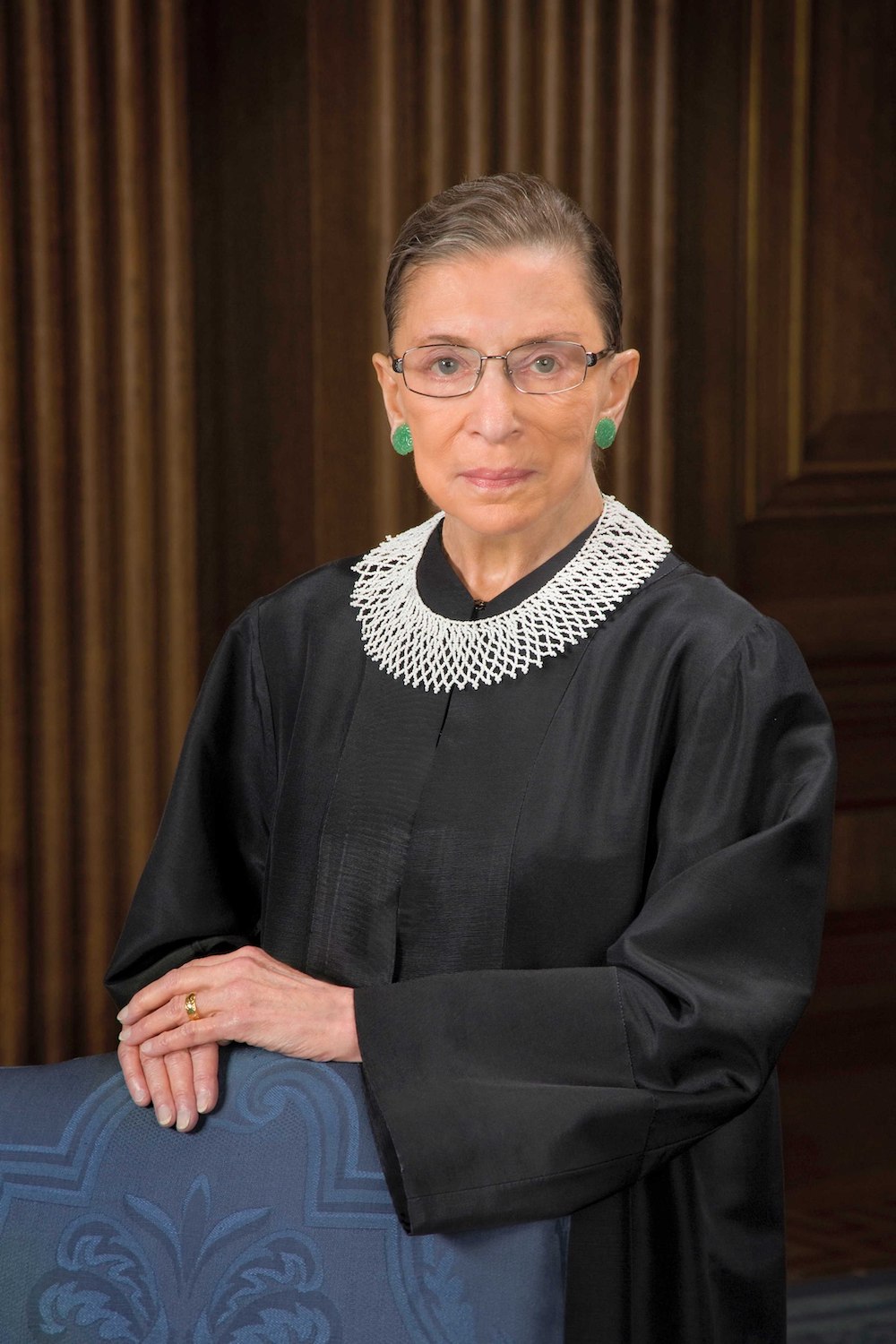

Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Associate Justice

Supreme Court of the United States

Chair, Judicial Advisory Board

American Society of International Law

Beloved friend and exemplar

Champion of justice and the international rule of law

REMEMBERING JUSTICE GINSBURG

The American Society of International Law mourns the loss of Associate Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who died on September 18, 2020. Justice Ginsburg enjoyed a close association with the Society, serving as chair of the Judicial Advisory Board from 2006 until her death.

Much has been written in recent days about the brilliance of her judicial opinions and her equally influential dissents, her skill as a legal strategist in advancing equal justice under law, and most of all, her transformation of the legal landscape as a pioneer for gender equality. Less widely appreciated is the important role she played as a defender of international law.

In an address at the Ninety-Ninth Annual Meeting in April 2005, she offered a vigorous response to the controversy over whether foreign law should inform U.S. constitutional adjudication. She took issue with the "notion that it is improper to look beyond the borders of the United States in grappling with hard questions," arguing, with characteristic humility, that "we are not so wise that we have nothing to learn from other democratic legal systems." In her view, "Foreign opinions are not authoritative; they set no binding precedent for a U.S. judge. But they can add to the store of knowledge relevant to the solution of trying questions."

In 2006, Justice Ginsburg succeeded Justice O'Connor as Chair of the Society's Judicial Advisory Board. In that capacity, she convened yearly meetings at the Society's headquarters at Tillar House with judges representing the thirteen federal judicial circuits to share information on the international legal issues before their courts, to hear from Society experts about current developments in international law, and to provide advice to the Society on the development of educational resources and programs for the judiciary.

Justice Ginsburg's last appearance before the Annual Meeting was as a surprise guest at the Women in International Law Interest Group (WILIG) Luncheon in 2017, where she presented the Prominent Woman in International Law Award to her close friend, ASIL's Honorary President, Judge Rosemary Barkett.

We invited the seven living former Presidents of the Society whose terms of office coincided with Justice Ginsburg's tenure as chair of the Advisory Board to share their remembrances of her and their thoughts on her legacy.

REFLECTIONS

It was not easy sitting side by side with an icon in the small confines of ASIL's conference room. Her diminutive physical size was out of proportion to a strength of character that I had never encountered before. Of course, all of us knew what she had accomplished in her life and what it meant that she was on the Court. But what we saw in those meetings was someone who was the focus of attention because of the expectations she generated. During those judicial board meetings her sharp gaze demanded non-evasive responses. It was amazing to see stellar judges, particularly those who had gone through the same experience on prior occasions and knew what was expected, acting like diligent students intent on showing that they had done their homework. Most brought detailed memos enumerating the various international law issues their courts had confronted over the most recent period. The judges did all this work not out of fear but because, at some level, the justice had convinced even the most skeptical of them that international law mattered to the rule of law—to what each had pledged to do as judges. Justice Ginsburg brought out the best in her colleagues at those meetings, as I am sure that she did on the Supreme Court. The Society, the world, owes her inestimable thanks.

José E. Alvarez

President 2006-2008

Thinking about it, I most recall Justice Ginsburg's remarks at the 2005 Annual Meeting, I think at the WILIG Luncheon, when she was introduced by Condoleezza Rice. I choose this still all-too-timely quote (as reported in the New York Times, 2 April 2005):

"The notion that it is improper to look beyond the borders of the United States in grappling with hard questions has a certain kinship to the view that the U.S. Constitution is a document essentially frozen in time as of the date of its ratification.… Even more so today, the United States is subject to the scrutiny of a candid world. What the United States does, for good or for ill, continues to be watched by the international community, in particular by organizations concerned with the advancement of the rule of law and respect for human dignity.

Lucy F. Reed

President 2008-2010

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg was and will remain a towering figure in United States law. She was a disciplined but creative legal thinker, a savvy and enormously effective advocate, and a judge whose decision making was infused in equal measure with respect for the rule of law and for human dignity. Her work as scholar, advocate, and judge had an enormous impact on United States law and, thereby, on the lives of all Americans.

From the Society's corner of the legal universe, we honor Justice Ginsburg with special appreciation for her commitment to the Society's mission and to international law as a critical component of the rule of law. She worked with us directly, of course, by leading our Judicial Advisory Board for many years. But more broadly, Justice Ginsburg demonstrated throughout her career a steadfast respect for international and comparative law. Her first brief to the Supreme Court in Reed v. Reed cited UN sources and German judgments. In her capacity as justice, she readily took account of non-U.S. authorities and international human rights law. And she demonstrated in the Medellín cases, in which I had the privilege of arguing before her, a deep respect not just for international law, but for the institutions and courts—the infrastructure—that undergird the international rule of law. That respect is reflected in her concurrence in the first of those cases, Medellín v. Dretke, in her observation at oral argument in Medellín v. Texas that the ICJ "can issue a binding judgment," in her joinder of Justice Breyer's dissent from the decision in that case to refuse to give effect to the ICJ's Avena Judgment, and again in her dissent from the final denial of the request for a stay of execution.

Combined with her strength of both intellect and principle, Justice Ginsburg brought great humility to her approach to the law—urging, in homage to foundational U.S. teaching, a decent respect for the opinions of humankind. In her words: "We are the losers if we do not both share our experience with, and learn from others." Would that we, and those who in the future occupy her seat on the Court, were all so wise.

Donald Francis Donovan

President 2012-2014

Justice Ginsburg sat at the Tillar House conference table discussing international law with federal and state judges for six hours on a Saturday in November 2015 – staying for a buffet dinner – as she had done annually as the long-time chair of ASIL's Judicial Advisory Board. I was honored to be part of that conversation as the Society's then-President – one of many times in which Justice Ginsburg generously shared her time, talents, and expertise to enrich understanding of international, foreign, and comparative law. Being a graduate and former faculty member of the law school where I teach, she had countless conversations on such topics with Columbia students, when she would often recall her own first post-law-school job, as a researcher with Columbia's Parker School of Foreign and Comparative Law – her first assignments, on the Swedish civil procedure code (!), prefigured a lifelong curiosity about similarities and differences among legal systems. She brought to the Supreme Court a nuanced appreciation of the many ways that international, foreign, and comparative law might (or might not) properly supply rules of decision within the U.S. legal system. She formed part of the group of Justices who paid close attention to international authorities in explaining the "evolving standards of decency in a civilized society." She wrote authoritative opinions on many topics central to the concerns of our Society, including interpretation and application of treaties, foreign sovereign immunity, and the continuing relevance of international comity when U.S. courts need to decide on claims involving deference to foreign and international processes. With the wisdom of her long life in the law, she had a deeply-grounded appreciation for how the procedural matrix for judicial decision-making shapes the ability of courts to give effect to enduring commitments to the equality and dignity of all human beings.

Lori Fisler Damrosch

President 2014-2016

That Justice Ginsburg was interested in international law was evident to me from her willingness to chair the Society's Judicial Advisory Board. But the question that intrigued me was why she was interested? Was it because she thought it was useful to know what cases were percolating up through the lower courts and might eventually come to the Supreme Court? Was it because a particular Supreme Court case had piqued her interest? Was it because of the debate over the relevance of foreign law to U.S. decisions? Or none of those? I will never be sure, but what I observed in the Advisory Board meetings during my tenure as ASIL President surprised me, particularly when Justice Ginsburg showed a keen interest in a comparative law discussion focusing on Mexico, and insight into civil law systems. I have since read about her early comparative work in Sweden and wondered not only how much that experience sparked her interest in international law, but also how it may have influenced her highly strategic thinking about gender equality. And I learned that when she appeared to be disengaged, with her head down and eyes closed, that was not to be taken at face value: at any moment, she could open her eyes and utter a piercing comment that made it abundantly clear she had followed every nuance of the ongoing discussion. A remarkable person, to whom we owe so much and who will be sorely missed.

Lucinda A. Low

President 2016-2018

From my encounters with Justice Ginsburg, enriched by the copious jurisprudence she generated during her long tenure on the Court, there is no question that she was progressive, enlightened, and nuanced in her approach to international and foreign law. To cite but one example, in her concurring opinion on race-conscious university admissions policies in Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 344 (2003), she turned to both the Convention on Racial Discrimination (to which the U.S. is a party) and the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (to which it is not) as guidance for considering the meaning of the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Aware that some believed foreign or international law should have no role in U.S. constitutional interpretation, she articulated a different vision, seeing those treaties as reflecting "international understandings" and those understandings as being in accord with a conventional, U.S.-centric analysis. Her method was calculated to persuade others into thinking in broader ways about rudimentary concepts of U.S. law and about the United States as a nation among nations. Her interest in international and foreign law led her to our Society, where she chaired for many years the annual meeting of our Judicial Advisory Board. During my time as ASIL President, she jumped at the idea of the Society reactivating a long-dormant program that would offer panels on international (and foreign relations) law for the annual conferences of the judicial circuits. Sadly, that program was just coming to fruition as the pandemic set in earlier this year. But like Justice Ginsburg herself, I expect that the Society will work tirelessly to continue such efforts and, indeed, should do so now in honor of the Justice's lifelong commitment to the rule of law—national and global.

Sean D. Murphy

President 2018-2020

I had the great fortune of first meeting Justice Ginsburg in her chambers to discuss her Chairmanship of ASIL's Judicial Advisory Board, a position to which she was deeply and personally devoted. It was awe-inspiring to look across the table at an icon, stealing as many glances as possible at the photographs, opera mementos, and artifacts from the world over that she had decorating her chambers, cataloguing the extraordinary life of an extraordinary person.

The world lost a champion for the rule of law last week. One of the reasons she was rightly revered is that she fought for women to compete fairly in the corridors of power—whether in law, business, politics, or the sciences—that have been dominated by men. The "Notorious RBG", a nickname she embraced, was not notorious to us; she was both familiar and unreachable, diminutive and toweringly potent. She argued groundbreaking cases in the Supreme Court even though no law firm would offer her a job. She showed that professional ambition can strengthen, not diminish, a loving marriage and deep bonds with our children. Her shared stories of what it is like to be the only woman in the room resonate deeply with many of us. Most of all, she showed how to be a change-maker, but did so with class and dignity, and by bridging ideological divides to form bonds with her ostensible opponents. When asked about her longstanding friendship with Justice Scalia, she famously said, "I disagreed with most of what he said, but I loved the way he said it."

Thank you, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Catherine Amirfar

President 2020-present

A PERSONAL REMEMBRANCE

In 2005, I was asked by American Bar Association President Michael Greco to chair a presidential commission on lawyers' civic engagement in their communities, called the "Commission on the Renaissance of Idealism in the Legal Profession." There were two honorary chairs: one was Theodore C. Sorensen, who had served as special counsel and speechwriter to President Kennedy. The other was Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Both participated enthusiastically in the work of the commission, and it was a highlight of my professional life to have the opportunity to get to know them over the course of our service.

In subsequent years, I would often see the Ginsburgs at cultural events in the city and at holiday gatherings at the homes of mutual friends. She was always a quiet presence and the center of attention.

When I came to the Society, I had the opportunity to work with the justice once again. I looked forward to my annual visit with her in chambers to give her news about the Society and to plan the Advisory Board agenda. I would bring her copies of our recent publications, which she would examine slowly and carefully, occasionally asking a question or making an observation.

Invariably, our conversation would turn to other subjects, from the artwork in her office to the many photos and mementos of family and friends. She had a particular interest in the abstract artist, Josef Albers, which I shared. It seemed to me that his abstract compositions exhibited something of the rigor and precision of her own work. Above all, we shared a love of music, including opera, which as all the world knows, was her passion. She would tell me about her visits to Santa Fe, Glimmerglass, and the Met to hear the latest premieres, and we compared notes on the Washington Ring Cycle, at which I saw her each night.

Her annual appearances at Tillar House were always a state occasion. In preparation for the meeting, we asked each member of the Board to prepare a written report of significant international matters that had come before their courts in the preceding twelve months. Invariably, Justice Ginsburg's report would be the first to arrive, a thorough and meticulous account of the matters she wished to discuss.

The day before the meeting, her security detail would arrive to inspect the building. As the day arrived, the staff and the caterers would make sure all was in readiness. At one o'clock, deputy executive director Wes Rist would greet her as her limousine pulled into the drive, and I would escort her up the stairs to the conference room. There, she would greet our president, the judges, and the other guests before calling the meeting to order. After the preliminaries, we would begin with her report on international law cases in the Supreme Court, moving around the table from circuit to circuit until all of the judges had had an opportunity to speak. After the reports, we would turn to the substantive presentations, with frequent questions and debate among the judges. Justice Ginsburg tended to say little during these discussions, allowing others to do most of the talking. But from time to time, she would pipe up, cutting to the heart of the matter with an acute question or observation. The meetings would conclude with a reception and dinner, an opportunity to relax with her colleagues that she always seemed to relish.

Justice Ginsburg had a special place in the life of the Society, and in our hearts. I shall cherish her memory.

Mark David Agrast

Executive Director 2014-present

ADDITIONAL REFLECTIONS

When I was executive director of the ASIL 1967-72, study groups of the Society regularly lunched at the nearby Cosmos Club. A study group included Alona Evans of Wellesley College, then the sole female professor of international law in the United States. Its chairman was Covey Oliver, a genial, burly professor of the law school of the University of Pennsylvania. He was not a man to be deterred by a doorman. He bypassed the ladies entrance and escorted Alona through the Club's front door. A few days later, I received a letter from the Club's secretary reprimanding me for a breach of the Club's rules and enjoining me to observe them in the future. I replied asking the basis for the letter and was informed that the Club's constitution required that ladies were to use the ladies entrance. I thereupon filed a motion to strike that proviso. A meeting of the membership was called to vote upon that motion and hundreds of members attended. The debate was vigorous. My motion was adopted. All this was reported the next day in The Washington Post.

Justice Ginsburg visited the International Court of Justice some 30 years later, when I was its president. As I was about to introduce her to my colleagues assembled round the oval table in the Court's deliberation chamber, she remarked to me that I "was the man who got women through the front door of the Cosmos Club." I congratulated her on the acuity of her power of recall.

Steve Schwebel

Former President, International Court of Justice

I had an unusual experience of Judge Ginsburg's deep interest in international law and foreign legal systems. In 2015, when I was serving as legal counselor at the US Mission to the European Union, the State Department Legal Adviser's Office asked me to assist in organizing a visit by the US Supreme Court to the European Court of Justice in Luxembourg. I accompanied five justices, including Justice Ginsburg, throughout the several day program, which included attending an oral hearing being held before the ECJ. During the hearing, I was seated in the gallery next to Justice Ginsburg. She sat quietly, hunched over, eyes closed. It was unclear to me at first if she was paying attention or not. The first presentation by counsel began, with the lawyer reading lengthy prepared remarks. Justice Ginsburg grew increasingly agitated, eventually plucking at my sleeve and whispering urgently, "Why aren't they asking questions! Why aren't they asking questions!" I quietly explained that it was the custom at the ECJ for judges to reserve their questions until the end of prepared presentations, and then perhaps a few of them would gently question the oral advocates. She shook her head in vigorous disgust, clearly having anticipated verbal engagement more along the lines of a Supreme Court oral argument. Justice Ginsburg was committed to understanding EU law and the perspectives it might offer on similar issues arising before the US Supreme Court, but the decorous style of oral advocacy in Luxembourg definitely did not win her approval.

Kenneth Propp

Non-Resident Senior Fellow, Atlantic Council

Not too long ago, I was fortunate to have sat next to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg at a small New Year's Eve dinner party. Our conversation quickly turned to women lawyers, and I mentioned Belva Ann Lockwood, the first woman to have argued a case before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Justice's eyes lit up. In addition to being a trailblazer for women before the Court, Belva had run for President of the United States in 1884 and 1888 under the National Equal Rights Party, long before women could vote. She was a delegate to peace congresses in Europe in the late 1800s. I mentioned to the Justice about how Belva, known for being outspoken, may have been why ASIL initially did not allow women as members. I cannot recall if the Justice knew about the Belva-ASIL link. I recall, however, the Justice speaking eloquently and at length, in her calm manner, about how Belva and others helped pave the way for us.

Susan Karamanian

Dean, College of Law, Hamad Bin Khalifa University

A Farewell to Ruth Bader Ginsburg, from a sister in law

The writer was the 2018 recipient of the Society's Goler T. Butcher Medal for outstanding contributions to international human rights law.

My friend, the incandescent Ruth Bader Ginsburg, was a jurist, a woman and a Jew. It was a defining combination that shaped her values, her passions and her vision, transforming her from distinguished Supreme Court Justice to iconic global metaphor.

She represented the aspirations of a new generation of women in the 1970s when she co-founded the Women's Rights Project at the American Civil Liberties Union and argued for gender equality before the Supreme Court; carried the feminist message into that court when she joined it in 1993; and developed it into a wider embrace of human rights during her supreme tenure. By the time she died on Sept. 18, she was the most recognized judicial name in my lifetime.

Hers was a remarkable but by no means predictable professional trajectory. At a time when women – rightly – considered themselves unwelcome as members of the legal profession, she went to law school. At a time when even if you became a lawyer, getting married – let alone having children – represented a choice that was seen to reflect an attenuated loyalty to your professionalism, she revelled in her marriage and parenthood. At a time when being Jewish – let alone Jewish and female – was a dubious calling card for employers, she embraced both exuberantly. At a time when being a feminist was seen as an assault on men and the status quo, she coaxed the law into an understanding that women had the same right to the status quo's choices as men. Then she changed the status quo.

It's hard to remember that there was a time when women like Justice Ginsburg had to figure out how to make the case for equality compelling; had to explain that women had the same right as men to work, to be paid fairly, to be free from violence and poverty, and to aspire; had to explain that there are not two sides to the case for equality, unless inequality is treated as a valid rebuttal; and had to explain that being fair to women is not being unfair to men – it is catching up.

Before there were widely publicized strategies for how to make your voice heard, your invisibility visible, your fears compartmentalized and your anger constructive, Justice Ginsburg followed the path illuminated by her own dreams, walked right past the censorious, the skeptical and the cynical, and cleared the path for others. She leaned in, she leaned out and she leaned up, but she never leaned down, except to help others. When she pursued justice on the Supreme Court, she was not only a judge, she was a judicial juggernaut who was catapulted into international orbit. And what catapulted her was the combination of a public responding with enthusiastic gratitude to her ever bolder judgments, and, on the other hand, the vituperative reaction of an increasingly regressive climate in which those progressive judgments were anathema.

The critics made their arguments skillfully. They called the good news of an independent judiciary the bad news of judicial autocracy. They called women and minorities seeking the right to be free from discrimination, special interest groups seeking to jump the queue. They called efforts to reverse discrimination, "reverse discrimination," or a violation of the merit principle, or political correctness. They said courts should only interpret, not make law, thereby ignoring the entire history of common law. They called advocates for diversity "biased" and defenders of social stagnation "impartial." They claimed a monopoly on truth, frequently used invectives to assert it, then accused their detractors of personalizing the debate. They said "feminist" was the scariest word in the English language, replaced ideas with ideology, and substituted analysis with labels such as "activist" or "legislators in robes" or "anti-democratic." This is the context in which Justice Ginsburg became a luminous avatar.

For her, there was no justice without respect for rights, no respect for rights without access to inclusion and no access to inclusion without compassion. Through her, the public saw how fragile the safety of their rights could be, and lionized her for recognizing the moral and social cost of injustice. And through her, the public saw how empathy and courage could vitalize judicial independence. When she wrote for the majority, as she did in striking down the all-male admission policy at Virginia Military Institute, she was leading the way. When she wrote in dissent, she was leading the resistance.

As human rights are being rolled back or cavalierly politicized in so many parts of the world, a world where the vulnerable have become more vulnerable, where prejudice poisons, hate kills, truth is homeless and lives don't matter, is it any wonder that Justice Ginsburg's legacy is so preternaturally cherished as a rebuke to all of the above? She is a reminder that democracy does not just depend on the will of the people, but on their humanity. And as someone who kept trying to protect their humanity, one dissent at a time, she is a reminder not only that justice is of the people and for the people, but that judges, at their best, will deliver it to them with fearless wisdom and transcendent hope.

Rosalie Silberman Abella

Justice, Supreme Court of Canada

President Bill Clinton's nomination of Judge Ruth Bader Ginsburg to the Supreme Court was widely acclaimed. For me, it was uniquely special because the president then nominated me to fill her seat on the D.C. Circuit. Happily, my robe now hangs in the robing room closet where the name plaque above mine reads "Judge Ruth B. Ginsburg."

Ruth and I did not know each other very well before then, but we soon became good friends, sharing hushed conversations, dinners with mutual friends, and many wonderful law clerks. Still, I could never escape the feeling that she always had her eye on me, curious to know if the fellow occupying the Ginsburg seat was up to the task. I hope she thought I was, for her opinions were always a model for me. They are powerfully reasoned; written with care, precision, and flair; and imbued with her deep respect for the parties before the court, especially America's most vulnerable. "Equal protection of the laws" was Justice Ginsburg's guiding principle and life-long mission.

David S. Tatel

Judge, U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit