Annex VII Arbitral Tribunal Delimits Maritime Boundary Between Bangladesh and India in the Bay of Bengal

On July 7, 2014, an arbitral tribunal established under Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) delivered its award in the Dispute concerning the Maritime Boundary between Bangladesh and India (Bangladesh v. India).[1] The arbitral tribunal delimited the maritime boundary between the territorial sea, the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and the continental shelf within and beyond 200 nautical miles (M) of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh (Bangladesh) and the Republic of India (India) in the Bay of Bengal. The arbitral tribunal determined the terminus of the land boundary/starting point of the maritime boundary in an area where the coast is highly unstable.

The arbitral tribunal’s award marks only the second time that a tribunal has delimited a continental shelf boundary beyond 200 M. It contributes significantly to the existing jurisprudence on the jurisdiction of international courts and tribunals to delimit a lateral outer continental shelf boundary pending consideration of submissions on the outer limits of the shelf by the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). The award also consolidates existing jurisprudence on concavity of a coast as a relevant circumstance in maritime delimitation. When combined with the 2012 judgment of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) in the parallel delimitation dispute between Bangladesh and Myanmar,[2] the award brings to an end decades of uncertainty as to the allocation of maritime entitlements within the Bay of Bengal.

Background

Negotiations on maritime boundaries in the Bay of Bengal between Bangladesh and its neighboring States of India and Myanmar had been ongoing since the 1970s.[3] Myanmar and India favored a delimitation based on equidistance. Bangladesh maintained that due to its position within the concavity of the Bay of Bengal, a delimitation based on equidistance would be inequitable, as it would cause a cut-off effect.

Having failed to agree on maritime boundary delimitation through negotiations, Bangladesh instituted arbitral proceedings against India pursuant to Annex VII of UNCLOS on October 8, 2009. Bangladesh also instituted Annex VII arbitration against Myanmar regarding the delimitation of their maritime boundaries on the same day, but that case was transferred to ITLOS in December 2009. ITLOS delivered its judgment in the Bangladesh/Myanmar case on March 14, 2012.[4] Unlike the Bangladesh/Myanmar case, here India did not agree to submit the dispute to ITLOS, so an arbitral tribunal was constituted to settle the dispute in accordance with Annex VII of UNCLOS.[5] India did not contest the jurisdiction of the arbitral tribunal to settle the dispute.

The Judgment

The arbitral tribunal first considered its jurisdiction over the dispute, in particular its jurisdiction to delimit the continental shelf beyond 200 M. On May 11, 2009, India made a partial submission to the CLCS claiming areas of continental shelf beyond 200 M in the disputed area. Bangladesh objected to the Indian submission in a note verbale dated November 29, 2009, claiming that the submission failed to comply with UNCLOS and the CLCS Rules of Procedure. On February 25, 2011, Bangladesh filed its own submission with the CLCS. India responded in a note verbale dated June 20, 2011, noting that the baselines drawn by Bangladesh did not comply with Article 7 of UNCLOS, which sets out the rules for the drawing of straight baselines.

The arbitral tribunal noted that both parties agreed that the arbitral tribunal had jurisdiction to delimit the continental shelf beyond 200 M, both parties had made submissions to the CLCS and neither party denied that there is a continental shelf beyond 200 M in the Bay of Bengal. Emphasizing that Article 76 of UNCLOS “embodies the concept of a single continental shelf,”[6] and “recalling the reasoning of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea in Bangladesh/Myanmar,” the arbitral tribunal stated that it saw “no grounds why it should refrain from exercising its jurisdiction to decide on the lateral delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200nm before its outer limits have been established.”[7]

The arbitral tribunal noted that the CLCS had decided to defer consideration of Bangladesh and India’s submissions such that “if the Tribunal were to decline to delimit the continental shelf beyond 200nm, the outer limits of the continental shelf of each of the Parties would remain unresolved.”[8] Accordingly, the arbitral tribunal considered that it had jurisdiction to delimit the continental shelf within and beyond 200 M in the areas where the claims of the parties overlapped.

The parties agreed that neither party could claim a superior entitlement to the continental shelf beyond 200 M based on geological or geomorphological factors in overlapping areas. Bangladesh had initially argued that it was entitled to a greater area of the outer continental shelf than India on the basis that the continental shelf in the Bay of Bengal was geologically the “most natural prolongation” of its coast. However, following the ITLOS judgment in Bangladesh/Myanmar rejecting Bangladesh’s argument that geological or geomorphological factors were relevant to determining continental shelf entitlement beyond 200 M, Bangladesh withdrew this argument.[9] The parties then agreed that entitlements beyond 200 M are determined by application of Article 76(4) of UNCLOS.

The parties agreed that the land boundary between the two States was to be used as the starting point of the maritime boundary and that the land boundary terminus should be determined by the application of the award of the Bengal Boundary Commission of 1947 (Radcliffe Award). However, the parties disagreed on what point represented the land boundary terminus under the Radcliffe Award. The Tribunal concluded that the land boundary terminus was to be located at the “midstream of the main channel” of the Haribhanga River. On the basis of a series of contemporaneous maps (including the map used in the Radcliffe Award), the arbitral tribunal concluded that the position of the land boundary terminus is 21° 38′ 40.2″N, 89° 09′ 20.0″E (WGS-84). The arbitral tribunal held that an exchange of letters between civil servants of the Governments of Bangladesh and India was not sufficiently authoritative to constitute a subsequent agreement on the interpretation of the Radcliffe Award within the meaning of Article 31(3)(a) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties.[10]

Bangladesh challenged several of India’s proposed base points on the grounds that they were located on alleged low tide elevations (LTEs), the existence of which Bangladesh disputed. In particular, Bangladesh claimed that South Talpatty/New Moore Island had permanently disappeared below the surface by the early 1990s. The arbitral tribunal held that, while LTEs may be used as base points for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea, it did not necessarily follow that they were appropriate base points for use by a tribunal delimiting a maritime boundary. The site visit carried out by the arbitral tribunal had not confirmed whether South Talpatty/New Moore Island constituted an LTE but, in any event, the arbitral tribunal held that it was not a suitable geographical feature for the location of a base point for delimitation purposes.[11]

The arbitral tribunal delimited the territorial sea using the equidistance method, finding that there were no special circumstances justifying a deviation from the equidistance line approach. Bangladesh had initially argued that given the instability of the coastline, the identification of base points was not feasible and that the construction of a provisional equidistance line was not an appropriate method of delimitation. Bangladesh considered that the use of a 180° angle bisector would be the most appropriate method of delimitation. However, following the decision of ITLOS in Bangladesh/Myanmar rejecting Bangladesh’s argument on the impossibility of identifying suitable base points due to coastal instability, Bangladesh changed its position and constructed a provisional equidistance line as an alternative argument.

Bangladesh argued that this line should be adjusted due to coastal instability and the concavity of the coast. The arbitral tribunal held that the concavity of the coast invoked by Bangladesh was not relevant to the delimitation of the territorial sea and did not produce any significant cut-off effect. However, as the land boundary terminus was not situated on the equidistance line constructed by the arbitral tribunal, the arbitral tribunal considered that the need to connect the land boundary terminus as identified by the arbitral tribunal to the median line constituted a special circumstance necessitating the adjustment of the provisional equidistance line.

Regarding the delimitation of the EEZ and the continental shelf, the arbitral tribunal considered that the three-stage equidistance/relevant circumstances method was the appropriate method to be adopted in the circumstances, in pursuit of an equitable solution. The Tribunal accordingly constructed a provisional equidistance line and then considered the relevant circumstances asserted by the parties.

First, Bangladesh claimed that as the coastline of the Bengal Delta is highly unstable this constituted a “special circumstance” warranting the adjustment of the provisional equidistance line. The arbitral tribunal acknowledged that the coastline was unstable, but did not consider this instability to be a relevant circumstance justifying adjustment of the provisional equidistance line. Second, Bangladesh argued that the “double concavity” of its coastline constituted a relevant circumstance. The arbitral tribunal concluded that, as a result of the concavity of the coast, the provisional equidistance line produced a “cut-off effect” on the seaward projections of the coast of Bangladesh. The arbitral tribunal considered that this circumstance necessitated adjustment of the provisional equidistance line in Bangladesh’s favor. Finally, Bangladesh argued that the dependency of its people on fishing in the Bay of Bengal required further adjustment of the provisional equidistance line. However, the arbitral tribunal concluded that Bangladesh had not submitted sufficient evidence of its dependence on fishing in the Bay of Bengal to justify any adjustment of the provisional equidistance line on that basis.

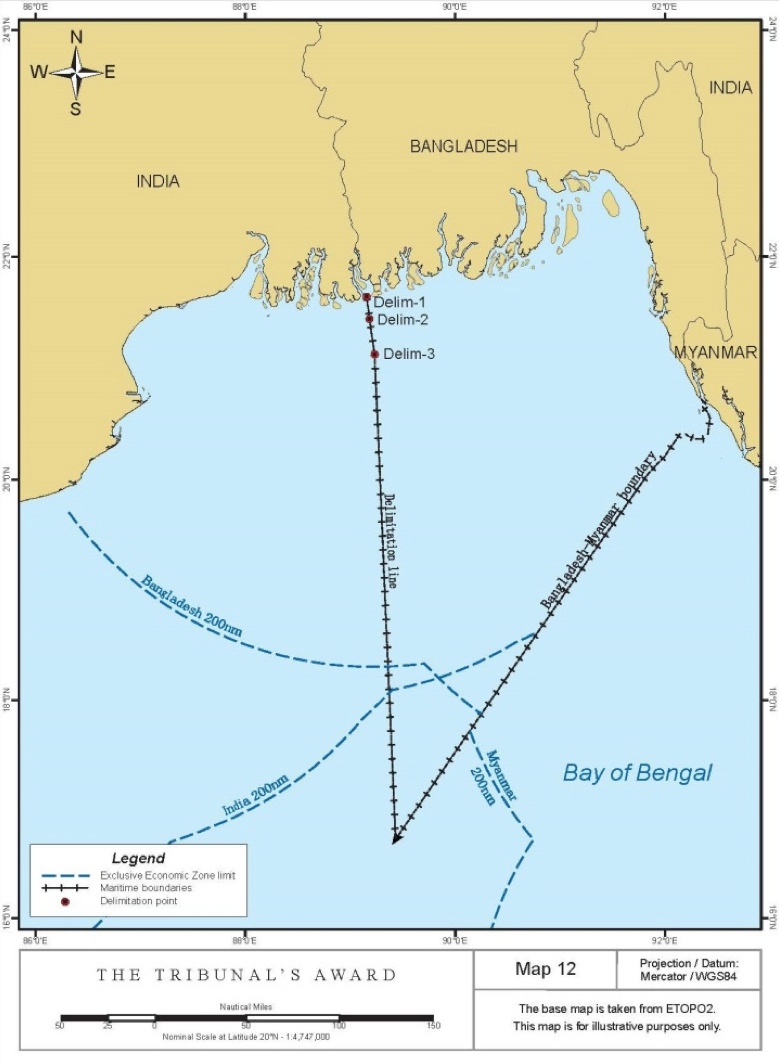

The arbitral tribunal applied the same methodology within and beyond 200 M, adjusting the provisional equidistance line into a simpler straight line to avoid a cut-off effect arising from the concavity of Bangladesh’s coast. At the final stage of the delimitation process, the Tribunal assessed the proportionality of the allocation of maritime zones by reference to the overall geography of the area, finding that no alteration of the adjusted equidistance line was required. The delimitation effected by the arbitral tribunal is illustrated below.

Grey Area

The delimitation line drawn by the arbitral tribunal created a so-called “grey area” beyond 200 M of Bangladesh’s coast but within 200 M of the coast of India. Since Bangladesh has no EEZ rights beyond 200 M, the delimitation line beyond that point only delimits overlapping continental shelf claims (that is the overlap between Bangladesh’s continental shelf beyond 200 M and India’s continental shelf within and beyond 200 M). As a result, east of the delimitation line in the grey area, Bangladesh has sovereign rights to explore the continental shelf and to exploit the “mineral and other non-living resources of the seabed and subsoil together with living organisms belonging to sedentary species,” while India has sovereign rights to the EEZ in the superjacent waters. The arbitral tribunal left it to the parties to determine practical arrangements for the exercise of their respective rights in the grey area.

A similar grey area was created by ITLOS in Bangladesh/Myanmar, where the seabed of the grey zone is Bangladesh’s continental shelf and the superjacent waters constitute Myanmar’s EEZ. The arbitral tribunal noted the overlap stating:

The present delimitation does not prejudice the rights of India vis-a-vis Myanmar in respect of the water column in the area where the exclusive economic zone claims of India and Myanmar overlap.[12]

This is in line with the statement earlier in the award that “the Tribunal must consider the Judgment of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea as res inter alios acta.”[13] Within the overlap of grey areas, both decisions recognise Bangladesh’s rights over the continental shelf, whereas India and Myanmar’s rights to the EEZ overlap.

The result is an unusual delimitation, where Bangladesh’s EEZ is entirely surrounded by the EEZ of India and Myanmar, but Bangladesh is nevertheless entitled to a continental shelf beyond 200 M, lying in some places underneath the EEZ of India and Myanmar.

In brief, the arbitral tribunal delimited the maritime boundary between the territorial sea, the EEZ and the continental shelf within and beyond 200 M of Bangladesh and India in an area where the coastlines of the parties are highly unstable. The issue of coastal instability is of increasing importance to maritime boundary delimitation, given rising sea levels and the disappearance of certain maritime features. In this context, the decision of the arbitral tribunal not to use an LTE as a base point for delimitation is significant. It is noteworthy that the arbitral tribunal did not take the future instability of the coastline into account.

The award of the arbitral tribunal very closely mirrors that of ITLOS in the Bangladesh/Myanmar case, which is unsurprising given that three members of the arbitral tribunal also contributed to the ITLOS decision. The award thus adds weight to the ITLOS decision regarding the competence of international courts and tribunals to delimit outer continental shelf boundaries.

About the Author: Naomi Burke, an ASIL member, is an associate with the law firm of Volterra Fietta.

[1] Bay of Bengal Maritime Boundary Arbitration (Bangl. v. India), Award (July 7, 2014), available at http://www.pca-cpa.org/showpage.asp?pag_id=1376. For additional analysis on recent maritime delimitation jurisprudence, see David P. Riesenberg, Recent Jurisprudence Addressing Maritime Delimitation Beyond 200 Nautical Miles from the Coast, ASIL Insights (Sept. 20, 2014), http://www.asil.org/insights/volume/18/issue/21/recent-jurisprudence-addressing-maritime-delimitation-beyond-200.

[2] Delimitation of the Maritime Boundary in the Bay of Bengal (Bangl./Myan.), Case No. 16, Judgment of Mar. 14, 2012, 12 ITLOS Rep. 4.

[3] Bay of Bengal Maritime Boundary Arbitration (Bangl. v. India), Memorial of Bangladesh, Volume I, 47 (May 31, 2011) , available at http://www.wx4all.net/pca/bd-in/Bangladesh's%20Memorial%20Vol%20I.pdf.

[4] Id.

[5] The three ITLOS judges of the Annex VII Tribunal had also participated in the ITLOS decision in the Bangladesh/Myanmar case.

[6] Bangl. v. India, supra note 1, ¶ 77.

[7] Id. ¶ 76.

[8] Id. ¶ 82

[9] Id ¶ 439.

[10] Id. ¶ 165.

[11] Id. ¶¶ 263–264.

[12] Id. ¶ 506.

[13] Id. ¶ 411.