The ICJ's Advisory Opinion on Climate Change: A Data Analysis of Participants' Submissions

Introduction

In March 2023, the UN General Assembly adopted a resolution asking the International Court of Justice (ICJ) for an advisory opinion on states’ obligations to protect the climate from anthropogenic greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and the legal consequences of causing significant harm to the climate. For the first time in history, all UN member states assented to a request for an advisory opinion. An unprecedented 91 states and international organizations subsequently submitted statements to the ICJ as part of the proceedings, far more than in any previous international court procedure. Indeed, since numerous briefs bundled views (notably those by the African Union, the European Union, and the Nordic countries) and many states are speaking before the ICJ without having submitted briefs, nearly all UN member states are participating in one way or another. Many UN member states are also appearing before the ICJ for the first time, in particular small island states. The advisory proceedings at the ICJ appear historic, even before the Court has handed down its opinion.

In early December 2024, the ICJ began hearing from participants in the advisory proceedings. With almost 60 percent of briefs, including more than 5,000 pages of argument, now available on the ICJ’s webpage, this Insight offers an initial data analysis of the written submissions currently available on four critical points of law: the advisory opinion’s scope, the principle of prevention of transboundary harm, whether human rights law imposes extra-territorial state jurisdiction, and the relevance of the law of state responsibility to violations of obligations concerning climate change.

Methodological Note

This Insight benefited from advance access to all participant statements and comments made to the ICJ. Switzerland provided me with early, confidential access to them to support its submission in the context of the advisory proceedings; they have been kept strictly confidential until the ICJ releases them to the public. After the ICJ President decided to make participants’ submissions progressively available - as they appear in court - the data analysis below is based on the 60 percent of briefs that are currently public.[1] While the remaining briefs are yet to be made available, the data analysis is unlikely to change significantly.

Based on the submissions, I created a coded spreadsheet with the support of two student assistants from the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland.[2] This data is openly accessible here with a brief explanation, as far as it has become public. It will be further updated once all written submissions are available.

In addition to the four salient questions that are discussed here, data was also gathered on 29 other questions in participants’ submissions. The publicly available spreadsheet also disaggregates participants’ answers to these questions into relevant groups (e.g., developed countries according to Annex I to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, least developed countries, etc.), thus offering further insight into the spread of views and opinio iuris that could not be presented in their entirety here.

The ICJ’s Position and the Formation of Custom

The ICJ’s advisory proceedings offer more than just a clarification of climate change law; they also present a unique opportunity to understand the formation of customary law. Both criteria for custom to form can be challenging in practice. While state practice is readily observable, it must be general. Opinio iuris can be hard to identify. The current advisory proceedings, however, offer an avalanche of expressions of opinio iuris. Nearly every one of the 91 statements and 62 comments submitted to the ICJ expresses a view contributing to opinio iuris, for instance, on the duty of prevention of transboundary harm and its applicability to GHG emissions. The ICJ’s advisory opinion, in turn, will not only articulate custom (or refrain from articulating it). It will also shed light on the meaning of participants’ expressions of opinio iuris. Thus, the advisory opinion will likely deepen our understanding of the formation of custom and add to the International Law Commission’s Draft Conclusions on the Identification of Customary International Law, which were released in 2018.[3]

Significantly, the ICJ will not be the first international court to speak on climate change.[4] During the written phase of the proceedings at the ICJ, the European Court of Human Rights in Klimaseniorinnen v. Switzerland [5] laid down the duties of Council of Europe member states in regard to climate change under the European Convention on Human Rights and the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) issued an advisory opinion clarifying how the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) applies to greenhouse gas emissions.[6] Moreover, a request for an advisory opinion on climate change is currently pending before the Inter‑American Court of Human Rights.[7] The ICJ is uniquely placed to fit these other courts’ rulings into the bigger picture of international law and address the international law on GHG emissions without prior substantive or geographical constraints.

Data Analysis

Scope of the Advisory Opinion

The first central question in the context of the ICJ advisory proceedings is the scope of the advisory opinion. Participants expressed views on this question in three principal ways. They addressed the scope of the advisory opinion directly as being either wide or narrow; they argued that the applicable law must be broadened beyond the core climate change treaties (the UNFCCC, the Kyoto Protocol, and the Paris Agreement) to include customary law, human rights law, the law of the sea, etc. (or may have inversely argued against such broadening); or they argued that the climate change treaties constituted lex specialiscrowding out other law (or not).

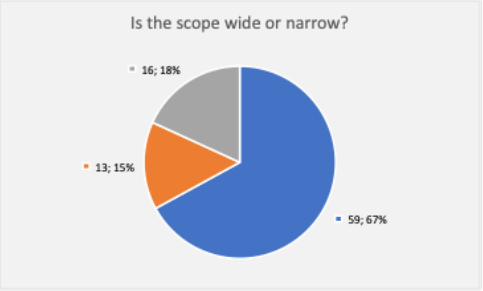

Figure 1 shows the statistical breakdown from the available written statements and comments to this first question.[8] Two-thirds of respondents argued for a wide scope to the ICJ proceedings, suggesting that the appliable law encompass more than climate change treaties alone. Substantial minorities of respondents, by contrast, took a narrower view of the scope or expressed no answer (or no clear answer) to the question (seventeen percent each).

Fig. 1: Scope of advisory opinion

blue: wide, orange: narrow, grey: no answer or no clear answer;

“x; y%”=number of submissions; percentage of total.

Principle of Prevention of Transboundary Harm

The ICJ spoke on the duty to prevent transboundary harm before. It addressed the duty on various bases in neighbourly relationships between states, subjecting it to a threshold of significant damage and point to point causation.[9] In the context of nuclear weapons, the ICJ opined that, “The existence of the general obligation of States to ensure that activities within their jurisdiction and control respect the environment of other States or of areas beyond national control is now part of the corpus of international law relating to the environment.”[10] Furthermore, in its first judgment, the ICJ considered, “every State’s obligation not to allow knowingly its territory to be used for acts contrary to the rights of other States” to be a “general and well-recognized principle.”[11]

In its advisory opinion issued after the conclusion of the first round of written statements at the ICJ, ITLOS clarified that the duty to protect and preserve the marine environment pursuant to Article 192 of UNCLOS and the duty to prevent, reduce, and control pollution of the marine environment pursuant to Article 194, respectively, applied to anthropogenic GHG emissions.[12]

In the ICJ advisory proceedings on climate change law, no participant so far argued that the duty to prevent transboundary harm, or a similar duty of diligence, was not part of customary international law. However, the crux lies in the question whether the customary duty of prevention of transboundary harm extends to cover anthropogenic GHG emissions. The findings of ITLOS on this point in its advisory opinion were sharply focused on the conventional law of the sea. If the ICJ in its advisory opinion more broadly finds the customary duty to prevent transboundary harm applicable, an obligation to mitigate and reduce GHG emissions will probably apply independently from the Paris Agreement, i.e., qua custom, to all states.

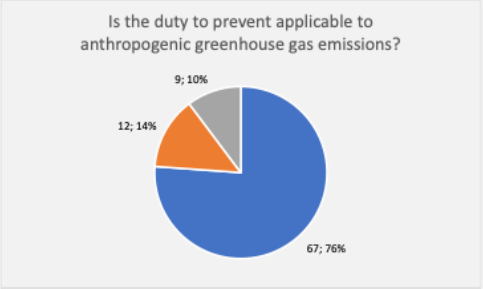

Figure 2 presents a statistical breakdown based on participants’ statements and comments (as far as available). It shows that almost 3/4 of the participants are of the opinion that the duty to prevent applies to GHG emissions, while nearly 1/5 explicitly expressed views to the contrary. Almost all participants answered this question.

Fig. 2: Applicability of duty to prevent transboundary harm to

anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions

blue: yes, applicable, orange: no, not applicable, grey: no answer or no clear answer; “x; y%”=number of submissions; percentage of total.

Though not reflected in Figure 2, it is worth noting that the United States[13] argued against the applicability of the duty to prevent, but made an eventualiter argument in case the ICJ found the duty to prevent applicable. The United States apparently thinks it likely that the ICJ will rule to this effect.

Extraterritorial State Jurisdiction

After the conclusion of the first round of written comments at the ICJ, the ECtHR held in Klimaseniorinnen that the rights to life and protection of family life according to Articles 2 and 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights implied certain obligations to mitigate GHG emissions. However, the ECtHR also underscored each state’s responsibility toward its own population in its own territory in matters of climate change, thus maintaining the limits of state jurisdiction developed in its case-law.[14] The ECtHR ruling on territorial state jurisdiction stands in contrast to an advisory opinion the Inter‑American Court of Human Rights handed down in 2017, which espoused a broader, effects-based approach to jurisdiction in case of transboundary pollution.[15]

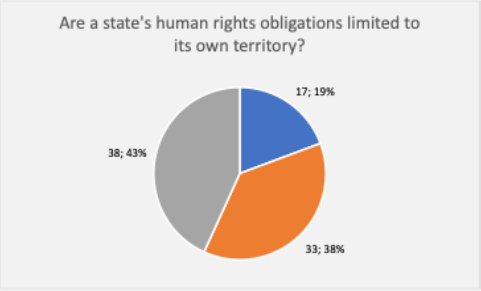

The ICJ addressed human rights previously. Sometimes it spoke on human rights extensively,[16] sometimes less so,[17] and sometimes not at all.[18] How far does states’ territorial jurisdiction quainternational human rights law go in the context of GHG emissions? Figure 3 shows the views of the participants in the advisory proceedings on this point, with approximately 2/5 of respondents favoring the view that human rights law would impose extraterritorial jurisdiction, while 1/5 did not. The remaining 2/5 of participants refrained from addressing this question.

Fig. 3: Limitation of state’s human rights obligations to its territory

blue: yes, limited to territory, orange: no, not limited to territory, grey: no answer or no clear answer; “x; y%”=number of submissions; percentage of total

Relevance of the Law of State Responsibility

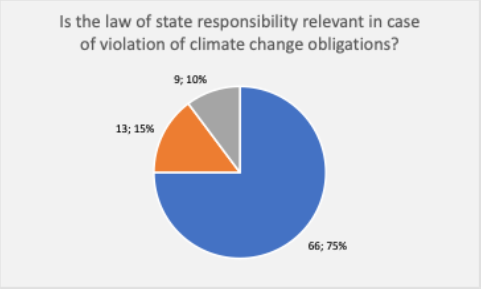

The Paris Agreement includes a follow-up mechanism that relies on non-adversarial, peer pressure, while dispute settlement in court is optional. Does this follow-up mechanism imply that the law of state responsibility is irrelevant in case of violation of the Paris Agreement and potentially applicable customary law? Does it crowd out state responsibility? The question is related to the potential lex specialis nature of the Paris Agreement and, thus, the scope of the advisory opinion (see Fig. 1). As Figure 4 illustrates, the predominant view amongst participants is that the law of state responsibility is relevant to violations of climate change law, while 17 percent considers it not to be.

Fig. 4: Relevance of the law of state responsibility in case of

breach of climate change law

blue: yes, relevant, orange: no, not relevant, grey: no answer or no clear answer; “x; y%”=number of submissions; percentage of total

Conclusion

With more than 100 states and international organizations addressing the ICJ’s advisory proceedings, this is the largest ever court hearing in international law. While this Insight presents data on participants’ submissions, it has refrained from interpreting it. How widespread does opinio iuris have to be to give rise to custom? How relevant is it that a majority of states believes something? Need such beliefs be representative of all states and the groups they belong to? It will be the ICJ’s task to provide answers, perhaps by interpreting the data. Even so, the breadth of participation in the advisory proceedings, while reflecting the magnitude of the challenge of climate change for international law, offers a unique opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the law and the mechanisms that give rise to it.

About the Author: Dr. Thomas Burri is a professor of international law and European law at the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland. He recently co-edited a book at CUP with Dr. Jamie Trinidad on the ICJ’s advisory opinion on the Chagos Archipelago and published a Nature-paper on a competition he organized to test the European Union’s new regulation on artificial intelligence (available here). Ariane Ducrest, a bachelor student, and Francesco Gravina, a PhD student, both at the University of St. Gallen, helped with encoding the data for this Insight.

[1] A few participants presented statistical data from first-round statements in their second-round comments. The data presented here is more comprehensive: it covers more questions and includes both participants’ statements and comments.

[2] Annexes to statements and comments were not encoded.

[3] G.A. Res. 73/203 (Dec. 20, 2018).

[4] National courts and international treaty-based bodies addressed climate change before, e.g., Netherlands v. Urgenda, Supreme Court of the Netherlands, 19/00135, ECLI:NL:HR:2019:2007, 2019 (Dec. 20); Klimabeschluss, German Constitutional Court (BVerfGer), Order of the 1st Senate, 1 BvR 2656/18, 1 BvR 78/20, 1 BvR 96/20, 1 BvR 288/20 (ECLI:DE:BVerfG:2021:rs20210324.1bvr265618), 2021 (Mar. 24); Teitiota v. New Zealand, Human Rights Committee, CCPR/C/127/D/2728/2016, 2019 (Oct. 24), Sacchi v. Argentina, Committee on the Rights of the Child, CRC/C/88/D/104/2019, 2021 (Sep. 22); Billy v. Australia, Human Rights Committee, CCPR/C/135/D/3624/2019, July 2022 (Jul. 21).

[5] Klimaseniorinnen v. Switzerland, App. No. 53600/20 (Apr. 9, 2024), https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/?i=001-233206.

[6] Request for an Advisory Opinion submitted by the Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law of Dec. 12, 2022, ITLOS Rep. 31 (May 21, 2024), https://www.itlos.org/fileadmin/itlos/documents/cases/31/Request_for_Advisory_Opinion_COSIS_12.12.22.pdf.

[7] Request for an advisory opinion on the Climate Emergency and Human Rights submitted to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights by the Republic of Colombia and the Republic of Chile (Jan. 9, 2023), https://www.corteidh.or.cr/docs/opiniones/soc_1_2023_en.pdf.

[8] I excluded the statement and comment of one participant from the data (Pacific Islands Forum), as it refrained from addressing the questions the GA asked.

[9] Gabcikovo-Nagymaros Project (Hungary/Slovakia), 1997 I.C.J. Rep. (Sept. 25), ¶ 140; Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay (Argentina v. Uruguay), 2010 I.C.J. Rep. (Apr. 20), ¶ ¶ 101, 197; Certain Activities Carried Out by Nicaragua in the Border Area (Costa Rica v. Nicaragua) and Construction of a Road in Costa Rica along the San Juan River (Nicaragua v. Costa Rica), 2015 I.C.J. Rep. (Dec. 16), ¶ ¶ 104, 118-119, 153-156.

[10] Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons, 1996 I.C.J. Rep. (Jul. 8), ¶ 29.

[11] The Corfu Channel Case (merits), 1949 I.C.J. Rep. (Apr. 9), p. 22.

[12] Supra note 6, ¶ ¶ 198 ff, 377 ff.

[13] Statement of the United States, ¶¶ 4.22 ff.

[14] Supra note 5, ¶ 443; see also Duarte v. Portugal, App. No. 39371/20 (Apr. 9, 2024), ¶¶ 177 ff, https://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-233261.

[15] The Environment and Human Rights, Advisory Opinion OC-23/17, Inter-Am. Ct. H.R. (Nov. 15, 2017), ¶ 101: “For the purposes of the American Convention, when transboundary damage occurs that effects treaty-based rights, it is understood that the persons whose rights have been violated are under the jurisdiction of the State of origin, if there is a causal link between the act that originated in its territory and the infringement of the human rights of persons outside its territory” (cited without footnote).

[16] Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, Advisory Opinion, 2004 I.C.J. Rep. (Jul. 9), ¶¶ 102 ff, in particular, ¶ 111 on extra-territorial jurisdiction, and ¶¶ 127 ff.

[17] Supra note 10, ¶ 25.

[18] Legal Consequences of the Separation of the Chagos Archipelago from Mauritius in 1965, 2019 I.C.J. Rep. (Feb. 25), ¶ 181.